×

11405 Old Halls Ferry Rd, Black Jack, MO 63033 is a single-family home listed for-sale at $70,000. Home is a 0 bed, bath property. Find 1 photos of the 11405 Old Halls Ferry Rd home on Zillow.

Illustration by Alex Williamson

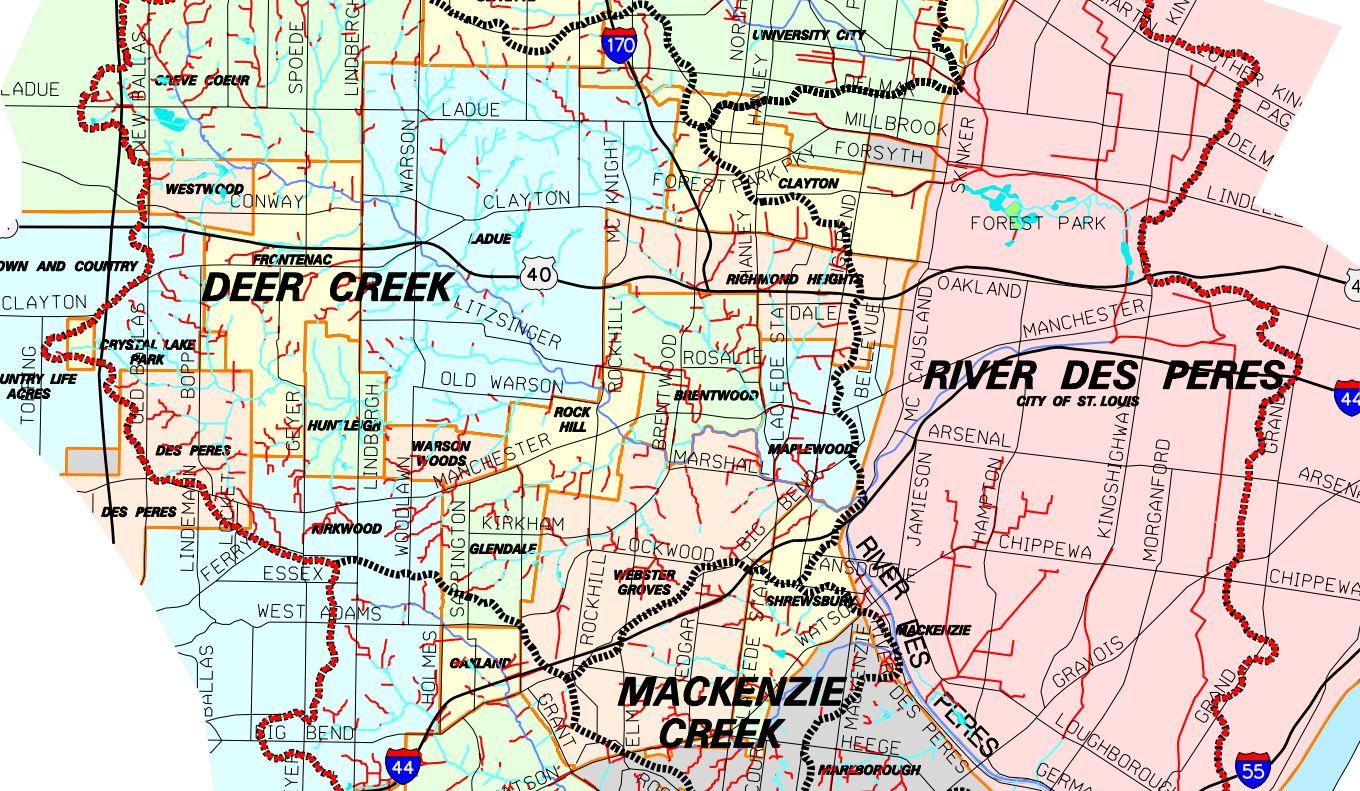

The whole world’s seen the maps. One starts out hot red or orange for the African-American population in the city’s core and cools to shades of Caucasian blue in the suburbs. Another uses stark black and white to show the Delmar Divide, named by the BBC (95 percent black north of Delmar Boulevard; almost two-thirds white south of it). Others trace that racial divide into St. Louis County, coloring in 90 municipalities like it’s election night.

What those maps don’t show are the ghost neighborhoods, once-black communities ripped out of both city and county. Gates and wrought-iron fences that segregate wealth. Tight ethnic enclaves. Blocks, gangs, and country clubs, each with their own exclusions. Two states sharing a metro area and vying for its resources.

St. Louis is divided along many lines. And race plays a role in every one of those divisions. It also determines our future, because if you make a transparent map of racial segregation and lay it over other maps—political power, cultural influence, health, wealth, education, and employment—the pattern repeats.

It’s 2014. Why does race still shape St. Louis? Why was segregation more dramatic here than it was in similar Midwestern cities? And why hasn’t it lifted as quickly?

St. Louis might be Midwestern, but its history is Southern. The city’s founders came upriver from New Orleans, and the Mississippi River kept our ties to the South alive through the Civil War. Unlike most northern cities, we had a 100-year history of slaveholding. Yet unlike most Southern cities, we avoided the crucible of civil-rights demonstrations. There had been an African-American population here almost from the start, but there was never much pressure for blacks and whites to mingle. Instead, there was what one scholar calls a “legacy of racial mistrust.”

Slaves had been sold on the steps of our Old Courthouse, and Dred Scott hadn’t won the right to buy his freedom there. When the case reached the Missouri Supreme Court, Judge William Scott wrote the decision—saying Dred Scott had no right to sue—and warned of “a dark and fell spirit in relation to slavery, whose gratification is sought in the pursuit of measures, whose inevitable consequences must be the overthrow and destruction of our government.”

Similar fears rippled through St. Louis’ white community. Its members were fine as long as the black population stayed at a stable 6 percent. But by 1900, St. Louis had more than 35,000 African-American residents, a population second only to Baltimore’s. Recent European immigrants worried that African-Americans who’d just come north in the Great Migration would steal their jobs. Others worried that neighbors with low-paying jobs would lower the value of their houses.

In 1916, St. Louisans voted on a “reform” ordinance that would prevent anyone from buying a home in a neighborhood more than 75 percent occupied by another race. Civic leaders opposed the initiative, but it passed with a two-thirds majority and became the first referendum in the nation to impose racial segregation on housing. After a U.S. Supreme Court decision, Buchanan v. Warley, made the ordinance illegal the following year, some St. Louisans reverted to racial covenants, asking every family on a block or in a subdivision to sign a legal document promising to never sell to an African-American. Not until 1948 were such covenants made illegal, after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on Shelley v. Kraemer, a case originating in St. Louis.

“Shelley was not the first African-American to move onto that block of Labadie,” points out Priscilla Dowden-White, associate professor of history at the University of Missouri St. Louis and author of Groping Toward Democracy: African American Social Welfare Reform in St. Louis, 1910-1949. “You had white neighborhoods where there might be two or three black families and no issue. It’s when whites in those neighborhoods began to sense that there was going to be more migration into that neighborhood—then you see the fear. ‘They will take over the neighborhood. The property values will fall.’”

In How Racism Takes Place, George Lipsitz writes that in St. Louis, “protection of white property and privilege guided nearly all decisions about law and policies that promoted the establishment of new small and exclusive suburban municipalities with restrictive zoning codes.” Those municipalities zoned for larger, more expensive lots and banned apartments. Realtors steered middle-class African-Americans toward certain parts of town and away from others.

“Both the City’s Real Estate Exchange and the Missouri Real Estate Commission routinely and openly interpreted sales to blacks in white areas as a form of professional misconduct,” writes Colin Gordon, author of Mapping Decline: St. Louis and the Fate of the American City. African-American homebuyers often had difficulty getting access to lower interest rates and down payments. The bravest fought the barriers with legal maneuvers, by using straw buyers, or by passing for white. But set against redlining, blockbusting, and exclusive zoning, those tools weren’t very effective.

Clarence Harmon, who would later become St. Louis’ second African-American mayor, recalls trying to buy a home in a North County subdivision called Paddock Woods in the late ’60s. “Well, sir, we are not selling homes to Negroes up here,” he says he was told. “There’s a case coming up before the Supreme Court, and they will determine whether we sell to any Negroes.”

Joseph and Barbara Jones had tried to buy a home in the same subdivision, but Alfred H. Mayer Company, the county’s biggest homebuilder, had informed them they could not. In 1968, the Supreme Court found in the Joneses’ favor, and Harmon moved into Paddock Woods.

Not every part of St. Louis wanted to be segregated, though. Gaslight Square was sited right on the north-south, black-white divide. University City, meanwhile, “formed its own residential housing service,” recalls writer and educator John Wright. “Shows you what can happen when you have a small geographic area and a well-educated Jewish population. They deliberately bought homes on the north side and sold them to whites and bought homes on the south side and sold them to blacks. The community would not yield to realtors and bankers.”

Most neighborhoods, however, did.

“Racism is a business,” Wright says, sighing. “If it wasn’t lucrative to chase people away, it wouldn’t happen. People make money off of it. And as long as people make money, the system flourishes.”

How have we managed to stay this segregated? Priscilla Dowden-White, an associate professor of history at the University of Missouri–St. Louis, has her own example, drawn from real life. When she and her husband went house-hunting in 1995, two decades ago, they popped into an open house near Tower Grove Park and met a real-estate agent, an older white man. He called, unsolicited, a few weeks later, saying he’d found “just the house for them” in Bel-Nor. When Dowden-White expressed no interest, he seemed angry, saying he thought they wanted to buy in North County. Instead, the couple made an offer on a house in the Skinker-DeBaliviere neighborhood.

When Dowden-White and her husband checked with the bank regarding FHA mortgage guidelines, the woman she spoke with expressed amazement that there were houses for more than $100,000 in the city. “There are houses a few blocks away that list at more than $1 million,” Dowden-White retorted.

Meanwhile, Dowden-White knew three other African-American couples who were house-hunting at the same time. They all wound up in North County.

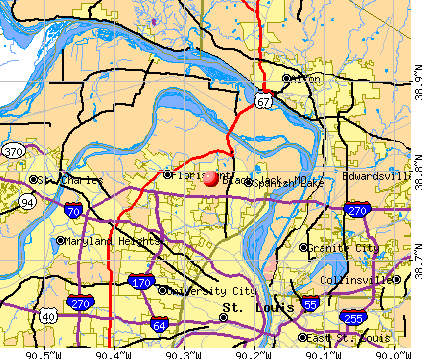

Urban geographers describe St. Louis as a donut hole—empty in the middle and encircled by doughy counties. Cities like Denver, Seattle, and Portland, Oregon, would be custard-filled, with appealing city centers and no gaps in the urban landscape. Here, white flight was followed by middle-class black flight, and historically black communities in the city were razed for the sake of “urban renewal,” highway construction, and tax-increment-financing redevelopment projects.

“We removed so-called slum neighborhoods,” says Michael Allen, director of the Preservation Research Office. “Mill Creek Valley, Chestnut Valley, Carr Square, we clear-cut. Then we demolished vacant housing in The Ville,” the neighborhood where Chuck Berry, Tina Turner, and Grace Bumbry grew up.

Sometimes, the policy was benign neglect until it was time to condemn. Sometimes, it was eminent domain. “We have spent enormous sums of public money to spatially reinforce human segregation patterns,” says Allen. “We have harnessed architecture as a barrier. And it’s been very frightening to see the result.”

St. Louis evicted 500 families, almost all of them African-American, from the Pershing-Waterman redevelopment area. To build Interstate 55, the African-American community of Pleasant View was destroyed, and the residents were given vouchers for Pruitt-Igoe. About 20,000 African-American families lost homes when Mill Creek Valley was declared a slum and destroyed. Interstate 44 toppled more African-American families from The Hill. The black community of Robertson was taken for airport expansion, as was a chunk of Kinloch. Parts of Meacham Park, North Webster, and Elmwood Park near Olivette were taken for redevelopment. More recently, Paul McKee anonymously bought up a large swath of the near North Side, then held community meetings to explain he was trying to rescue the area and get TIFs for redevelopment.

Virvus Jones, a former St. Louis comptroller, assessor, and alderman, believes TIFs should be allocated differently. He mentions the TIFs granted in the city since 1993—a total of 137, six for addresses north of Delmar. “So the premise is that south of Delmar is more blighted than north?” he says. “They say, ‘That’s where people want to develop.’ I say, ‘No, that’s where you subsidize people to develop.’ You have half the city that looks bombed-out and the other half prospering, parts of it looking like Georgetown. Do you really think that’s a sustainable model?”

Race, overlaid with economics and a fear of crime, has influenced myriad decisions that shaped the metro area’s landscape: where the MetroLink stopped. How far south Interstate 170 went. Why a public housing project wasn’t relocated to Jefferson Barracks in South County. Why it’s been so hard for St. Louisans to mentally include the Metro East in the region.

The region’s black-white divide shows up in the lopsided governance of municipalities (not just Ferguson), banks, corporations, and cultural institutions. Civic Progress has one African-American member, and the executive council of the Regional Business Council has no African-Americans. The Regional Commerce and Growth Association has two African-Americans on its executive committee. St. Louis’ major cultural institutions have a smattering of African-American board members but no African-American CEOs.

St. Louis is landlocked and weighted by history. Long-established in-groups have cliquish traditions. All that familiarity can leave us a little wary of the unknown. And because we’re so segregated, much is unknown. “You’ve still got people who won’t even go to Forest Park—they read somewhere that someone got raped in 1901,” Wright says with a low chuckle. There are South Siders proud to say they’ve “never been north of 40.” North Siders afraid to drive west lest they get pulled over. Young girls warned never to “go over to the East Side.” Kids in Monroe County cautioned about crime across the river. Refugees from Africa warned upon arrival that our black neighborhoods are dangerous.

Jones characterizes the prevailing white attitude like so: “‘As long as we can keep them over there in that colony, north of Delmar, north of 70, we will be all right.’ As long as we stay invisible, there is no problem. As long as I don’t see it, it doesn’t exist. I’d rather have you hate me, because if I don’t exist, I’m not a human being. I’m an inanimate object.

“That’s what has developed over the years,” he continues. “People think they can be protected. We have these invisible barriers that keep us from poor people and black people.

“The expectation of the system that in 50 years, you were going to correct 250 years of slavery and 150 years of Jim Crow, was probably not realistic.”

The Ferguson riots are now famous. But before August, St. Louis was famous for not rioting.

Oh, there was 1917, but that was over in East St. Louis, Illinois. European immigrants were terrified that the 10,000 or so black workers streaming in from the South would take their jobs. Instead, many black migrants found that the jobs they’d been promised were nonexistent. Sensationalist newspaper stories announced that unemployed black people were on a rampage of crime, buying guns and planning a race war.

Hell broke loose in that riot, which exploded after a rumor that a white man had been killed by a black man. The riot went on for nearly a week, most of the violence targeting African-Americans. A baby was thrown into a fire. A man was hung from a telephone pole in downtown St. Louis, his scalp ripped off. There were reports of people being thrown off the Free Bridge (now called the MacArthur.)

Then came the Fairgrounds Park riot in 1949, on the first day that black children could swim in the pool. Several hundred white adults surrounded the fence, and at day’s end, violence broke out.

By the time of the Jefferson Bank civil-rights protests in 1963, St. Louisans had learned containment strategies.

Jones remembers getting picked up at high school to join the protest, because he was too young to be locked up in jail. “We got arrested,” he says, “and my mom came to pick me up, and the second time she said, ‘Look, I’m gonna lose my job. I can’t keep coming to pick you up. I’m not upset at what you are doing, but you might have to stay there for a while.’ ’Cause my father worked two jobs.”

He also remembers a newspaper reporter telling him, years later, that both the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and the St. Louis Globe-Democrat had a policy of not writing about civil-rights activities. Wright says many black activists were given jobs, because then they wouldn’t be able to afford to get arrested and miss work.

“St. Louis has responded to race matters in more conservative ways than other places have,” says Gerald Early, director of African & African-American Studies at Washington University. “I also think St. Louis has had a kind of complacency, because it’s never had this kind of violence until now. A certain complacency, and maybe even assumptions on the part of the white establishment that this isn’t going to happen here.”

Harmon agrees. “I’ve lived here all my life. Almost all politics locally is viewed from the prism of race and class. Our civic leaders would say, ‘St. Louis? We don’t riot. We don’t do that.’ We have become so complacent over the status quo that we were not expecting this. You look at the protesters: young men with no jobs, lack of education, no prospects. What we have seen in St. Louis is the outward migration of the working class—the factory workers, the small-business owners. White people fled what they didn’t understand and didn’t want to expose themselves to: the problems of a disenfranchised group of people who were uneducated, with a lack of prospects. And the people who are late coming to these communities, a lot of whom we saw in the protests, are those people who have few prospects.”

Most days—until recent events in Ferguson, at least—St. Louisans have kept their heads down and walked forward, as though they’re walking into a gale-force wind, when racism’s mentioned. It’s a fact of life here, but one that’s hard to talk about without sounding inflammatory or clueless.

And that, in itself, is a form of segregation.

Black Jack Mo Zoning Map 2017

Historical Timeline

1820: The Missouri Compromise allows slavery in Missouri.

1821: Missouri enters the Union as a slave state, but eventually supplies almost three times as many troops to the North.

1846: Dred Scott’s case for freedom is dismissed on a technicality.

1857: The Missouri Compromise is declared unconstitutional, foreshadowing the Civil War.

1863: President Abraham Lincoln issues the Emancipation Proclamation.

1913: A committee of whites calls for “Legal Segregation of Negroes in St. Louis.”

1916: The legal segregation initiative passes.

1917: Buchanan v. Warley: Racial segregation ordinances are ruled illegal. The city resorts to racial covenants.

1917: The East St. Louis race riot: At least 39 African-Americans die, with one man hung from a telephone pole.

1934: The Federal Housing Administration is created to insure private mortgages; it gives D ratings in many black neighborhoods.

1948: Shelley v. Kraemer: The St. Louis case ends racial covenants nationwide.

1949: Black children are permitted to swim in Fairgrounds Park. Whites surround the pool fence, and a riot breaks out.

1950: Over the next two decades, 60,000 African-Americans will leave the city.

1954: Brown v. Board of Education overturns Plessy v. Ferguson to desegregate U.S. schools.

1954: Attorney Frankie Freeman takes St. Louis’ Housing Authority to court for racial discrimination in public housing—and wins.

Black Jack Mo Zoning Map Nyc

1956: Pruitt-Igoe is completed. Its failure is apparent almost immediately; the public housing will be demolished within two decades.

1963: Protests outside Jefferson Bank persuade the bank to hire white-collar workers of color.

1964: Percy Green II and Richard Daly protest discriminatory hiring for work crews building the Gateway Arch.

1968: Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co.: Racial discrimination in housing is declared illegal.

Bellefontaine Neighbors Mo

1972: Civil-rights activist Gena Scott unveils the Veiled Prophet during the ball.

1979: After Black Jack tries to block a multiracial apartment complex, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit reaffirms the Fair Housing Act of 1968.

1983: The St. Louis County school districts agree to accept black students from the city on a voluntary basis. State funds are to be used to bus the kids to the county for an integrated education.

1989: Confluence St. Louis examines the city's racial divide in a report. Few of its recommendations are heeded.

1993: Freeman Bosley Jr. is elected the first black mayor of St. Louis.

1997: Clarence Harmon becomes St. Louis’ second African-American mayor.

2014: The police shooting of Michael Brown and ensuing protests draw global attention. Amnesty International sends 15 human-rights observers—the first team it’s ever assigned within the U.S.—to monitor claims of police violations in Ferguson.